Interview: OpenTRV

As part of the Indie Manufacturing project we are talking to (aspiring) indie manufacturers, suppliers and support organisations to work out what the challenges are, see how people have overcome them and to work out what we don’t know.

We interviewed Damon Hart-Davis from Open TRV early on in our research, back in January 2016, as part of checking our assumptions in the challenges or problems they face. Below are the edited highlights of that interview.

Andy: Hi Damon. Let’s jump right in. Can you tell us who you are and what you’re making?

Damon: So Open TRV Ltd as we are now and Open TRV the Open source Project are here to help cut carbon. Our vision is to help Joe Everyman or Everywoman cut carbon painlessly – often this will be in a domestic environment so the first thing that we’re tackling is domestic space heating because we reckon that in the UK it accounts for something like 20% of the UK’s entire carbon footprint and half of it is wasted. That’s 5 or 6 billion quid a year that people needn’t be spending on their gas bills if they did their heating better and the mega tonnes of carbon that go with that. We’re trying to make it cheap and easy and simple for people to save a bunch of that.

Andy: So what is this TRV ‘thing’? Is it hardware?

Damon: At this stage we are building a smart radiator valve with optional interconnectivity with the internet and to your boiler. Lots and lots of people can write new lovely pretty shiny apps but we’re firmly in the world of the Internet of Things - although we only worked that out later in the game. We are at the interface of hardware and smartness to improve things that are already here. We may have other domestic energy efficiency things in future, but they are almost all likely to have a hardware element to them.

Andy: So how many people are in the team?

Damon: It depends how you count them – I think if you count all the bodies including part-timers there are about 10 but you know we’ve had 1 go and 2 arrive within the last 7 days for example.

Adrian: That’s still a reasonable number for maker stuff. There are still a lot of one-person bands or a couple of people tops out there.

Damon: So there’s only 2 of us that are full-time. I wouldn’t want to be getting ideas above our station and thinking we are some sort of mega corp! In reality it’s like having 5 or 6 people full-time including the two principals. We’re not tiny but we’re certainly not huge. Our business plan is to get huge in terms of size of market but probably never to grow hugely in terms of size of core team.

Adrian: So are you expecting to licence the designs to other people?

Damon: Ah now that’s all in our business plan and I would have to kill you afterwards (laughter)!

Adrian: Fair enough that’s fine.

Damon: The quick summary is - every business has the problem of making enough money to survive or grow and we want to be a growth business. We want to scale. We’re actually aiming with this product to be on the vast majority of Europe’s 500 million domestic radiators. We’re aiming for a product deployment size in the 100’s of millions. It has to be done cheaply too so that people can afford to do it. In order to maximise adoption we will basically do whatever gets the most units deployed and that may be a combination of licensing, manufacturing and so on. I can tell you our key performance indicator is mega tonnes of carbon saved not the number of yachts owned by the principals.

Adrian: Great. A nice social aim for the business.

Damon: Yes, we are a Social Enterprise.

Our second KPI is health improvement though it’s difficult to measure that. But it does mean that we have two key markets mapped out that we’re going for. The first of which is social housing and the second is retail to get the scale. The exact way we deal with those – well – things will change as we move forwards. We will be doing manufacturing of some degree as we move forwards and we will see how it splits as we go forward.

Andy: Can you talk us through a little about where you are up to and particularly about the design and production processes you’re going through at the moment?

Damon: The Open Source Project is about 3 years old, maybe a bit more.

We went through a couple of iterations where we got engineering samples which are functionally correct. We did the first few on stripboard. We’ve gone through a large number of design iterations with software and hardware, pretty well absolutely everything out in the open.

In that spirit we even 3D printed our boxes etc. etc. The issue is that if we are going to hit our target scale we think we need to be able to hit our £10 per valve pricepoint – and that’s retail price. You aren’t going to do that by 3D printing boxes taking 6 hours each so we have to get slick into manufacturing.

Cost reduction engineering has been a big part of our work and will continue to be for the next few years. We’ve designed the software, we’ve designed the hardware, we’ve built boxes and we’ve now got a mechanical valve design and we will continue to iterate that. We’ve got plastics to be made in Shenzhen and we’ve got the boards being elsewhere. I think the boards are being populated in Andover but I’m not quite sure whether that’s going to happen yet. Basically you go wherever is right to get costs reasonable and to get reasonable reliability.

Adrian: You say you got volume through Shenzhen and obviously you’re looking for cost reduction all the time. I am wondering how you select the number of units? Do you run a number of iterations to the prototype?

Damon: Probably something like megalomania is the answer – we’re trying to maximise impact – not that I’m any sort of expert you understand but the standard thing you do is you look at the total addressable markets in all places where the technology might apply. You look and see what part of that you might be able to service, the serviceable markets. We have a reasonably good idea of the number of radiators in the UK and we’ve done lots of research to try and establish those numbers for the rest of Europe for example and our vision is we want to be able to say ‘we want to be on 80% of those domestic radiators to get a big chunk of carbon savings’.

Adrian: And then you start having conversations with people about those sorts of volumes?

Damon: Part of the business plan plan is to try and plot a trajectory to say ‘in 30 years time we want to be on 400 million radiators across Europe and be the standard thing that people go and replace their radiator valves with.’ Today we have – including the engineering samples from the field – 20 out there so far, it’s currently costing us probably £50 or £60 to make one of these valves. We need to get down to £3. The business strategy and the manufacturing and engineering strategy for getting us from A to B all have to go hand in hand because we need to be a growth company. You need to generate the cash to do the R & D to get you the next cost reduction, to get the next tooling done and all this other stuff. You need a growth plan which gets you there.

Adrian: What about getting the idea to market?

Damon: We are not saying here’s our better mousetrap – how can we force it on people? What we’re saying is if we want to make the bigger saving in carbon this is how we’re going to do it. This came out in a discussion with the then the Chief Adviser of [DECC] (http://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-of-energy-climate-change) saying what the better way to cut carbon would be. I was asked to lead a workshop on smart heating and it looked like domestic heating efficiency in the UK would be a real winner. Having done that you say “well how am I going to tackle that market? What are the numbers if I’m going to get traction in there?” If I’m going to move the needle we don’t want to be a boutique operation and from that you say “right, in 30 years time we want to be on 400 million radiators – how can we get there from here?” The technology is only about 20% of the issue I think.

Adrian: A lot of the IoT stuff is speculative I suppose – the tech’s there, it just needs to be cheap enough.

Damon: So one of the issues, if you have a solution and go looking for a problem you tend to get slightly artificial stuff. We are driven by what we need to do to maximise carbon savings and what technology can we pull in to solve that problem at an appropriate price point. I’ve given a number of talks where I’ve said that we will have succeeded when IoT is beige boxes which no-one pays any attention to. That’s our view of the world. We’re all about building incredibly dull beige boxes which just work and are cheap.

Adrian: I’m not quite sure that I’m stuck on beige boxes – it would be good to have a few nice items as well but I see what you’re getting at!

Damon: We sell the nice ones to John Lewis at a premium (laughter) I kid you not. We’re happy to sell to people who want to pay for the aesthetic but that won’t get us volume. To get volume it has to be dull and boring. I’m very happy to sell to a small group of people who care about the design aesthetics or equally that other small niche group of makers and programmers but that’s not the product which will move the needle in terms of carbon even if it’s got more or less the same stuff inside it.

Andy: Can you tell us where are you up to with China and how did you go about identifying people in China?

Damon: At the moment we have tools being prepared. The expensive bit about injection moulding is getting the moulds done. Each piece of plastic you need normally needs a separate mould which costs about £6K each. We started off with a design at the beginning of the year with 10 pieces - £60K worths just for the tooling! Now we’ve got the tooling costs down and those tools are been worked on. I have sitting right here beside me an entire set of plastic parts with the motor and all that sort of stuff inside it! We’re tweaking the plastics at the moment so we’ve just placed an order for a thousand worm drives which is just one little bit of the plastic thing. We then do a modification and they send us a run of 500 of everything.

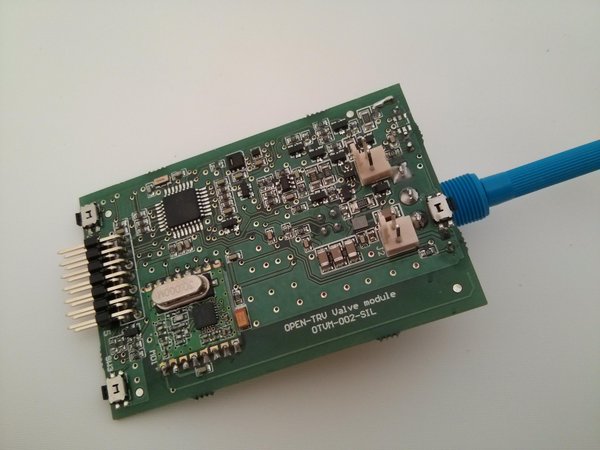

The boards that are going to go inside we’ve had for a year or so. We’re building a new run of them now. We’re tweaking some component values and omitting some things but we’ve had the electronics for a year. The particular board that fits inside and the firmware will need to wait until I’ve had some of the first real solid ones in my hand so I can build and tweak some stuff. But we have a working model – it all works in the bits that we have. It’s a bit of a Frankenstein’s monster thing but it is amazing because Mark and I aren’t mechanical guys we’re electronics and software guys so having real working mechanics is amazing.

The plastics is really interesting as well. I knew it was expensive 30 years ago. I did a job before Uni where we built a toy robot that went on Wogan amongst other things and the cost of making a mould hasn’t changed. It costs many grand to make a single mould but to actually have a design in my hand now which is doing our thing is just amazing. It’s not perfect - we’ll improve it, cost reduction, space reduction, everything but you know, it’s there.

Adrian: That must be amazing.

Damon: We don’t know if the outcome will be failure and embarrassment or it will just work and no-one will realise just how much we’ve sweated over it.

Getting back to the China question and how we found them the real answer is a year or so ago we got a grant from the people who are in the accelerator for Climate Kic, we talked to designers who helped put the initial designs together for us. We then spent twelve months looking for people to take it forward and we found a bunch of people in Andover. Smart people, PDC they’re called and they made the intros for us in China. You can’t, as Westerners, just turn up with no contacts in China and expect anything to work. For a start you can’t get into the country without an invitation. So you need to have an intermediary.

We looked hard for electronics and plastics companies so we could do them here or in Eastern Europe. My last start-up did all the development in Malta which is half the price of doing it in London but the quality was just as good as China. Our current thinking is that plastics from China, electronics in the UK and assembly in the UK is the way it’s going to go, but we will look at that every single time.

Andy: Is that purely based on cost?

Damon: Cost and expertise and quality control. You know ideally everything would happen next door to my house. If there’s a problem I can go round and say “stop doing that, do this” - but we don’t get that choice. Having things assembled by Westerners with Western notions in terms of what is important in terms of quality and delivery and close to hand is helpful for higher value bits. The plastics stuff is cheap and is probably best done in China but honestly it will change for each iteration we do. We will have to inspect all those decisions again. The UK, Eastern Europe and China are probably the hot candidates.

Adrian: One of the things we’re investigating are the kind of supply chains that give people options to go from being a craft person making everything by hand through to outsourcing everything to China. We want to know if there’s a middle way that uses some local kind of supply chain ‘stuff’. It feels like you’re right in the middle of all that.

Damon: You know the first one we built ourselves – I’ve got pics. If you go to my Twitter feed the picture in the background is pretty much the first board I hand soldered on Veroboard, that was the electronics and the software was put onto there myself, you know, that was all mine. We moved up a bit mechanically. We went to 3D printing boxes. We bought in a third party valve so we didn’t have to do that bit ourselves. We have had manufacturing done in bigger rounds repeatedly. With one of the boards we did 2 lots of 40 which was quite big for us at the time and we’re probably going to have another chunk done by the same people, that’s up in Yorkshire – very close to where Wuthering Bytes is interestingly – and now if we’re going to get set up for scale for any significant volumes the big question is if we go up to about 500 we deal with the vacuum casting and if we go beyond 500 we probably do injection moulding for the plastics. You know there’s a whole range of stuff but I think we are actively using items at many levels in that scale right now.

Adrian: Yeah, it feels like you’re totally riding the curve, working out how you you decided on the numbers, this sort of size for this stuff from here or when you really do have to go off to China. You pick the right production technique for the volume you’re targeting at that point.

Damon: Volume and speed and budget are the determinants of what technique you use. When we want to get PCB’s made really cheaply we you use a company called itead in China and it costs about a dollar a board all in - including postage - but you have to wait 2 or 3 weeks.

Adrian: Given your target is carbon saved – did that factor into your manufacturing decisions? Is that something you’ve been taking into account as you’ve been doing it? Wondering about materials and suchlike?

Damon: Yes and no. It’s awfully difficult. I have been talking to a number of people who really really care and know about upcycling and recycling. You say “we’ll use a biodegradable plastic” – but if it doesn’t destroy the plastic that’s bad it gets into the recycling chain and it destroys the entire batch it’s in. There are non-obvious things there but just from the starting point we are as parsimonious with energy ourselves, so that, for example, you replace batteries as little as possible. The valve we are making will work with rechargeables rather than disposable alkalines.

We try to be parsimonious with our materials and not do anything horribly toxic so there’s obvious things like being RoHS compliant and so on. For the first batch we can’t solve everything but we’re trying. We’ve got our hearts in the right place and we’ve got some of the steps but as we go along we’re going to have to look at the design for re-use. For example we’d like our devices to last 10 years but this first batch might not last 3 months, in effect we’re almost testing the waters but at a larger scale. So we do care about it, doing it right and doing it ethically and not adding to landfill and energy problems but we can’t solve all of those problems right off the first time.

Adrian: I have the same sort of concerns and I wonder every now and then should we be doing any electronics at all?

Damon: If I can save 6 billion pounds worth of gas in the UK alone for less than that in electronics with a retail mark-up… It is far from perfect but price is a very rough indicator of carbon and other environmental costs. So if I’m saving money robustly in this area for people then I’m quite possibly reducing their environmental footprint. That’s a kind of rule of thumb.

Adrian: Save all the gas first and once we start getting on top of the design for that we can iterate further on.

Damon: Yes, and we’re going to grow. We’re making 500 units this time. So, OK, that’s not going to make any difference to anyone. There are more iPads chucked away on a single day in Croydon probably. We don’t have any real grossly outrageous components in here but yes, as we go along with cost reduction, environmental impact reduction will be one of our targets, it might even be a formal target.

Adrian: Is it all Open Source?

Damon: Almost. So here is one of the dilemmas though when you are wanting to be a successful growth company and you want to do a public good then you have a double or a triple bottom line so you’re not just optimising profit on its own. In order to have a profit and be able to get some hope of hitting that 4 hundred million units target we’re talking about we have to have protectable business IP. I’m not a huge fan of patents even though my brother’s a patent attorney but I’d love to have my name on a patent. We think the right thing to do for us generally is give away as much as we can. The quote from Wikipedia is “give away a recipe to build a restaurant” but give away the bits which don’t cut off your nose to spite your face and retain enough elements for a while to generate your revenue so people can’t just rip you off. For example our previous design of the plastics and mechanics is published but we won’t be publishing this version for a little while. The code will generally all be published but we may retain some supersecret sauce for a little while to use for individual clients who have private arrangements with us. We might do a deal with Company X and they may say – can you do us a valve which has a unique selling proposition so we wouldn’t let that out – not for a while at least.

Adrian: I’ve been wondering about my designs and wanting to Open Source them but at the same time you need to make a profit to be able to keep going and in the end that does more good because you keep churning stuff out. So maybe you need some Open Source licence that says stuff will be Open Source but lag by x?

Damon: Yes but just don’t publish it. We’ve got various things, we’ve got copyrights, we’ve got trade secrets, we’ve got patents. So I think patents are just horribly misused at the moment and toxic and I want to be neither a borrower nor a lender as it were and I’ve taken a fair amount of advice from a number of people on that and I’m feeling fairly confident about that.

Andy: You mentioned a few people/organisations earlier that you got advice and support from. Can you elaborate a little on that?

Damon: I’ll be doing lots of people a dis-service as there are too many to list, but a really great experience has been Climate-KIC. They are very helpful people, very supportive - not blindly throwing money around or anything – they’ve said no to us at least as often as they’ve said yes when we’ve asked for things. Other than providing some cash, they’ve held what they call masterclasses for things like sales, for example, or negotiation or dilemmas you get in as a start-up… all from really top class experts in the field. The first revision of our business plan was done very much as coming out of those classes and some of their business coaching. Now we’ve completely revised our view of the world again but we wouldn’t have got to where we have without them.

There have also been things like Innovate UK’s Launchpad project - they were very helpful in coaching us (and the rest of the entrants) in the sorts of things they wanted to see and the plan that they would like. It sounds a bit odd but what they’re doing is saying we want you to succeed, we don’t want you to struggle. For those of us who were successful they also brought us into the Government Growth Accelerator where we had another round of coaching by, you know, a real grown up who’s done real business. And she was fantastic.

Ignite are another – we are applying to Ignite for funding. They are the social impact arm of Centrica and they helped us understand that we really are a social enterprise because we actually care about doing some good stuff, we just want to have a growth business to do it at scale.

There have been a bunch of people like that and lots of individuals and some will help for free, some come chat with us regularly. One is always on his way back from Bulgaria or somewhere - usually buying a company or something exciting and he takes half an hour every week to talk us through stuff – Rob W if you’re listening, wonderful, thank you very much. So many individuals have been great.

Andy: So, you’ve used the more formal route but this is a project looking at maker networks – how important are they to your business?

Damon: So although I’m clearly not Richard Branson I’ve been doing start-ups for 30 years and my first one – when we went to raise finance – there was only one guy in the country who would even talk to you if you weren’t asking for a million quid and there was no community around that and you were generally considered some kind of weirdo inventor type if you did anything inventive at all.

Roll forward 30 years and it’s trendy and there’s money being chucked at it by the previous government, possibly a bit less by the current administration. There’s loads of things like Maker groups and there’s lots of tools – things like Skype and GitHub and SourceForge and lots and lots of ways to make it much easier to do the technical and business networking aspect.

And it’s a long time, getting on for 20 years, since I had a formal office. I work from my place, my business partner works from his place and we have staff we deal with remotely or we have a meet up – one of the advantages of the Climate KIC accelerator is we have access to the Imperial College Incubator and we meet there every Wednesday. So the hot-desking aspect is another aspect that makes this start-up so much easier to do today.

The combination of all that and the monetary support and the coaching support is just astonishing and if we fail to deliver this business it will be entirely our doing; it won’t be because anyone was cruel and withdrew support from us.

With the tools and the environment it’s as fun as it’s ever been over the last 30 years as far as I can tell. I would say this is the best environment it has ever been to get (particularly a tech-based) start-up off the ground. – for all those reasons.

Andy: Damon, thank you so much for your time.

Damon: Thank you

Adrian: Good luck