Indie Manufacturing, a Talk at OSHUG

At the 2016 Open Source Hardware Camp, part of the Wuthering Bytes technology festival, Adrian gave a talk about the Indie Manufacturing project.

Here are the slides, and notes on what he anticipated saying - they won't match the talk exactly. The talk was recorded - we'll update this when it's available online.

Hello, I'm Adrian McEwen. You may remember me from such OSHUG talks as (What is) The Internet of Things? (OSHCamp 2012) or Risking a Compuserve of Things (Wuthering Bytes 2013). It's lovely to be back.

I connect strange things to the Internet - for fun, as products for my company, and for others.

Most of this year, the biggest project I've worked on has combined all of those.

The Royal College of Art is doing research into how makerspaces, fablabs, etc. might feed into or enable new ways of manufacturing and organising manufacturing.

As part of that we’ve been looking at how the maker community can hook into local supply chains.

This is the blurb from the project website, so you don’t need to read all of it, but the two phrases at the top help me explain our approach.

The received wisdom is that you can’t make things in the UK – it’s fine for craft, handmade goods with a high cost, but beyond that you have to raise lots of money and go to China.

We wondered if there was a middle way. Are there smaller firms hidden away that can help us build things at a medium scale – 100s or 1000s of units rather than 10s of 1000s? Can we look to different materials and processes to help that?

I love this quote from Saarinen. It's something I think about in how we approach things at DoES Liverpool: a person inside a makerspace; a makerspace in a community; a community across a region...

How does the knowledge developed by the members of the makerspace get captured and shared to make the next person's job easier?

The makerspace allows people to pool resources to gain access to machinery that it doesn't make sense—or is too expensive—to own individually. And that lets someone build one or two of almost anything. What do the people who want to scale up to 100s or 1000s of items need? Does it make sense for the makerspace to provide that?

There's lots of information being built up in maker communities, and shared freely. But only if you know who to talk to, or who needed which production process in which of their projects.

Our maker bus ratio is a problem. If we can find ways to improve that, we'll get more resilience and help people find solutions to their problems faster to boot.

I don't scale. How do we encourage more of the connectors, the mavens?

So, what did we do?

We interviewed a number of people from the community who are going through the transition from maker-of-one-or-two-things to manufacturer.

They were each at a different stage, and generally each approaching it in a different way, so it was interesting to compare their experiences.

We have a couple more to publish, but the interviews are on the #IndieMfg website.

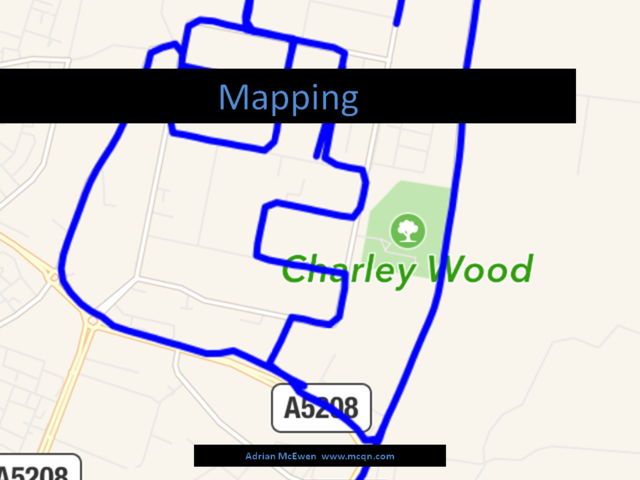

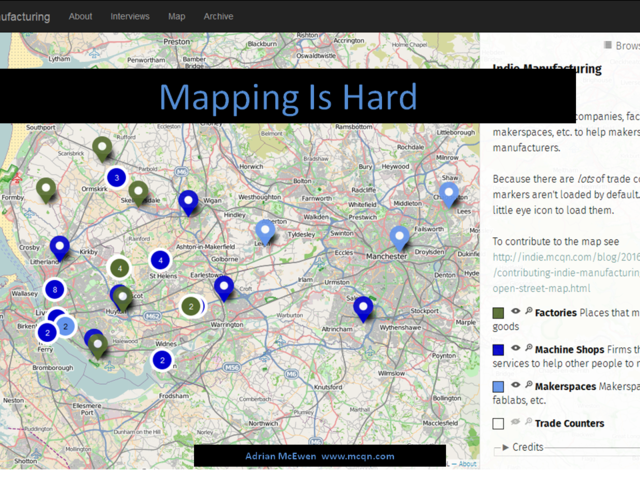

We also did some mapping - of suppliers, makerspaces, factories, and the like.

A combination of trawling round industrial estates and encouraging fellow makers to contribute the places they've used in their projects. From trade counters, to engineering companies who can CNC parts for you from metal, PCB manufacturers, die-cut box makers, and more.

When you talk to the people running these firms, they often tell you that they're happy to work with individuals and small companies.

However, it can actually mean that they're happy to work with you once you reach a certain scale. If you turn up wanting a run of 800 PCBs that's worth their while, but if you only want 50, say, then it doesn't make sense to reconfigure their production line.

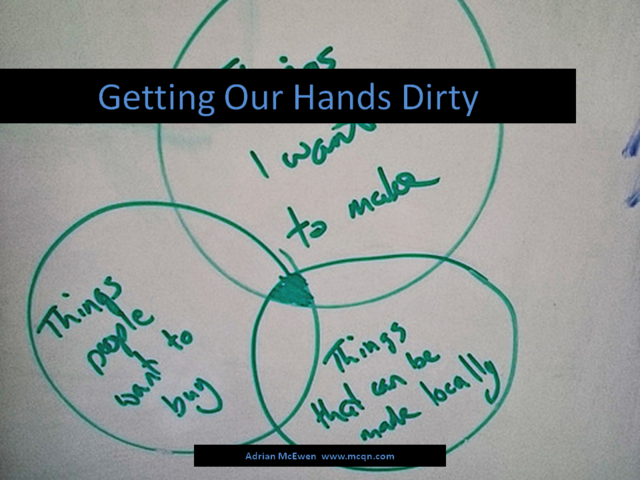

To flush out these kinds of issues, we also wanted to get our hands dirty and actually run the process of making something ourselves.

So my company, MCQN Ltd, took one of its product ideas and is putting it through a(n initial) production run of a couple of hundred units. That would let us test these supplier assumptions and no doubt throw up other problems that we wouldn't think of.

The project officially finished at the end of July, so what have we found out?

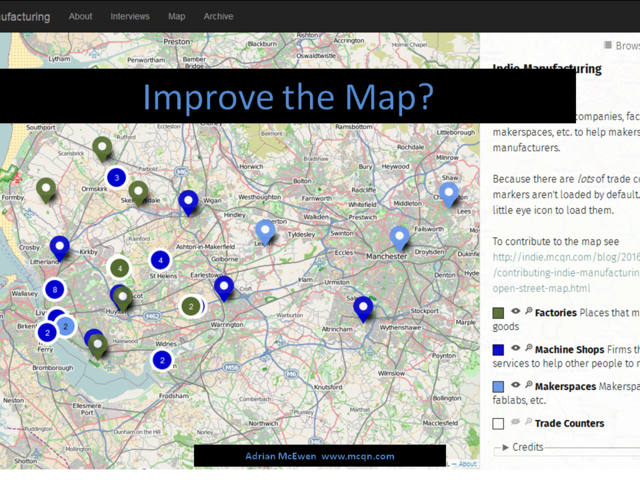

Getting people to add to the map is tricky. Most people we spoke to had at least one supplier or company to add to the map, and were happy to share what they knew. However, the barrier—or just the perceived barrier—around adding it to Open Street Map was too great for nearly all of them.

The other method we used was trawling round industrial estates. That, in itself, is lots of work; there are lots of them and you don’t find out how good any of the firms you're adding to the map are. It can also be pretty intimidating—we joked that maybe we needed to include a "testosterone factor" in our mapping, to capture how approachable any of the firms or locations are.

If we were doing it again we’d spend more time trying to find what the community knows, as the first step. And most likely concentrate more on how to help the community supply that data more easily.

There were challenges on the software side of the mapping too.

Using Open Street Map as our datastore meant involving another community. That introduced an additional layer of negotiating to work out which tags to use, but will give us a better chance of longevity. I think with hindsight we were a bit too worried about getting things wrong, and so didn’t talk to them as broadly as we should.

And the tools to get data out of Open Street Map are almost there, but there are a few missing pieces. Overpass Turbo (which lets you query the data) and uMap (which lets you build maps) work really nicely together, but the performance isn’t there for it to "just work".

Once you start looking for firms in the UK who make things, you find them all over the place and making all sorts of things. They're just invisible to anyone outside their industry.

In theory that sort of information is captured by SIC codes. These are the industry classification codes that all limited companies declare to Companies House. However, in practice they're useless. As a company there's no indication at all of what they're for, so if you're anything like me then you'll have picked whatever seemed plausible when you first registered the company and then just skip the "do you want to change them" part of your company return each year, regardless of whether the company has moved into a new area.

This seems to be an open secret, but it's still the only tool that anyone trying to look at a bigger area—researchers, government departments, council support organisations, etc.—uses.

Making hardware takes a long time.

We had some discussion about what real project we should make and decided that an Internet of Things device would be best as that (a) plays to my strengths and (b) would let us attack some processes less common in small-volume products.

That was always going to be a stretch in a 6-month project. So, surprise, surprise, it’s not quite ready.

We've got a prototype, and a lot of the suppliers sorted out for obtaining the parts and doing the manufacturing. Still more things to tie down, but we've a good idea of the short-list at least for the remaining tasks.

One thing we've found through making an actual product is that, for off-the-shelf components, particularly the items of lower value, they aren’t made in the UK any more.

The ESP8266 module that’s the core of the product comes from China. I remember back when I was CTO of Goodnight Lamp (before that shifted to GSM for comms), we struggled to find WiFi modules for under £12/unit. And that was without a processor.

The ESP8266 modules, which have both WiFi and processor, are a couple of dollars in quantities of 1!

Similarly, we couldn’t find any bell manufacturers in the UK beyond the expensive, high-quality musical-instrument-grade bells.

Alibaba.com makes it easy to find worldwide suppliers now – it turns out for electronics that’s usually China, but for bells India seems to be the place to be. Alibaba makes it easy at the start, but there is still some complexity hidden behind that. They hook you with an easy search box, but there’s still a fair bit of back and forth in working out which supplier to use, and then you have a new world of shipping terms to get to grips with. And you might need to work out the world of freight-forwarders to get your parts shipped by sea.

Being able to swing factories into action, and kick off things being delivered to docks and put in containers and sent round the world to you, just from your browser and a few emails is amazing! But there are also times where visiting the factory or tapping into the knowledge and skills from a phonecall to the manufacturer are invaluable. Particularly if you need to customize anything.

Once you’ve got a map, then you can start.

Pick the most likely place to offer what you’re after and visit them. They’ll tell you who might really be able to do what you want. Go and visit those people.

Repeat.

The local enterprise partnership, “the council”, enterprise centres, etc. are all organisations that people assume will be able to help you find local partners and manufacturers.

Generally they can’t. They don’t have a list of all the companies on their patch - they make guesses from SIC codes and the like, and know some of the people who come and talk to them.

They want to help, but a combination of being encouraged to run at large scale generic solutions and not knowing how to talk to groups like makerspaces mean that the opportunities are often missed.

To mis-quote Steve Ballmer, it's all about people, people, people!

The best contacts and advice come from members of the community sharing their experiences and address books. We need to find ways to grow the community, infect more of business with our culture of openness and sharing, and help the people in support organisations who "get it". Find ways to expand the number of people in the network, not try to replace the people with software.

So, what next?

The end of the project isn't the end of the product. MCQN Ltd will be finishing off the remaining work to get the Ackers Bell on sale for all your bell-notifications-of-Internet-events needs.

Head to the Ackers Bell catalogue page on the website and sign up to the mailing list to be first to hear about further developments.

We also want the map to live beyond this project. Our intention was always that we'd just be seeding the dataset and then it would be up to the community to continue adding to it and extending it.

So if nothing else, people can add new places to Open Street Map and they'll appear on the map.

It would be good to find ways to make it easier for people to submit new items, and improve the information displayed—and the filtering—on the map. That will need some work on some of the Open Street Map tools, which I'd like to find time to do. There's no more funding in this project for that, so volunteers and/or funders who want to get in touch would be more than welcome.

And given that the rest of the site will become more of an archive of the project, we're not sure that the Indie Manufacturing website is the best place to hold the map for the future.

An obvious place, particularly for those of us in the North, would be the UK Maker Belt Association website.

If nothing else, we want more making, more manufacturing, and more sharing!

Thank you. Any questions?